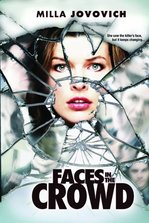

A young woman named Anna sees her world turned upside down when she becomes the sole witness to a murder and also suffers an injury that leaves her unable to recognize people by their faces, including the killer. Struggling with prosopagnosia, also known as "face blindness", Anna must learn how to navigate a world full of friends who look like strangers, and strangers who could be killers. Can she see people for who they really are before the killer comes for her?

Neuropsychological Review

Face Blindness: Losing Others, Losing Yourself

Caitlin Potter

There is nothing so comforting as recognizing the face of a loved one amongst a veritable sea of strangers. Imagine what life would be like if you lost the ability to recognize a friend, family member, and even yourself! ...

After the attack, Anna and Bryce consult Anna's doctor. He shows her two photos and asks if she sees the same face in each; when she replies affirmatively, he tells her they're actually two different people. The doctor says she's symptomatic of prosopagnosia, or "face blindness", and mentions that it is caused by a lesion on the temporal lobe. The doctor doesn't describe Anna's brain damage specifically; he only offers the general cause. He then points out the region on a lateral (or side-view) MRI scan of (what we must assume to be) Anna's brain. Even though the doctor seems to point somewhat indiscriminately at the MRI, he does accurately indicate the general region of the temporal lobe. In fact, the temporal lobe contains the Fusiform Face Area, a region of the brain which is specifically tuned to recognizing faces in particular (Gazzaniga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2009). However, the doctor implies that the temporal lobe is solely responsible for facial recognition. While surprisingly sufficient for a "whodunit" thriller, this is too general of an assertion. In actuality, most cases of acquired prosopagnosia result from trauma to the temporal, occipital, and even the parietal lobes of the brain and their underlying structures (Gazzinaga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2009). Throughout the movie, Anna remains a high-functioning person with no reported cognitive or health issues other than prosopagnosia. While prosopagnosics can potentially maintain all other cognitive abilities, someone with a head trauma as severe as Anna's would most certainly have additional brain damage and symptoms in addition to face-blindness (Gazzaniga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2008). Lastly, the doctor informs Anna and Bryce that confirmed cases of prosopagnosia are "extremely rare". In reality, the disorder is much more common than originally thought, affecting 2.47% of the general population (Kennerknecht et al., 2006).

Anna is referred to a neuropsychiatrist, Dr. Langenkamp, for a formal diagnosis. During the first consultation, Dr. Langenkamp comes across as absurdly insensitive. After observing an MRI scan of Anna's brain for several silent seconds, the doctor asks, "what was I supposed to see, exactly?", and we're left wondering if she's incompetent or just unprofessional. Frustrated by the doctor's cryptic dialogue and unclear diagnosis, Anna leave the consultation. Dr. Langenkamp warns Anna that she must get used to people's faces changing and that she shouldn't underestimate the seriousness of her condition. While technically correct, Dr. Langenkamp seems a stereotypical portrayal of an eccentric, even pseudo-scientific psychiatrist. As time passes, the stress of Anna's condition weighs on her; she even fails to recognize her own father, mistaking him for Tearjerk Jack. Anna resigns herself to her new reality and returns to Dr. Langenkamp, who instructs Anna to use distinctive markers like tattoos, gait, or distinctive facial features to identify people. This is sound advice, as face-blind individuals learn to use individual, distinctive facial features as well as the sound of a voice and even the sense of smell to identify and recognize people (Zillmer, Spiers, & Culbertson, 2008; Sacks, 1985). Therein lies a glaring short-coming plaguing the film: Anna consistently fails to recognize even her closest friends and family by their voices. Even her father and her love interests aren't vocally recognized. In actuality, the voice is perhaps the most useful and distinctive marker to someone struggling with any blindness; Anna never sufficiently utilizes it. Dr. Langenkamp offers Anna a bleak but realistically poignant explanation of the life a prosopagnosic should expect, claiming people will call her "rude, forgetful, stupid" and resent her for not recognizing them. This is unfortunately true for many face-blind people, some of whom shun interaction with friends and family to avoid inevitably offending them (Gauthier, Behrman, & Tarr, 1999).

Throughout the film, many allusions are made to faces and the emotional weight they carry. There are repeated shots of Anna's Facebook profile littered with personal photographs of herself and her friends. When Anna first awakens after the attack, the viewer is subjected to a similar sense of disorientation, as Bryce, Nina, and Francine are now portrayed by different actors. Cinematically, this effectively evokes empathy for Anna and justifies her alarm. The casting trick continues throughout the movie, and although it conveys the disorientation of face blindness, it grows confusing and tiresome. Anna's different relationships represent the various levels of understanding and compassion fielded by those suffering from prosopagnosia. Bryce becomes less and less sympathetic to Anna's struggles, ultimately dumping her after finding a journal with detailed descriptions of the ties he wore each day. Anna's friends Nina and Francine downplay the severity of her condition. Detective Kerrest is initially callous, yet becomes Anna's advocate and protector. Eventually, Anna realizes that she has "regained" the ability to recognize only Kerrest's face. This is used for dramatic effect to enhance the romantic connection, but it's an inaccurate portrayal of the progression of prosopagnosia. While many face-blind people can exhibit unaffected functioning in all other cognitive areas, there is no aspect of the disorder that allows specific faces to be recognized while precluding others (Gazzaniga, Ivry, & Mangun, 2009; Kennerknect et al., 2006). The film establishes a connection between Anna and Kerrest based on a very emotional love. This doesn't mean that love can magically and selectively cure prosopagnosia, but there is evidence that the experience of strong emotion can cause prosopagnosics to subconsciously recognize certain faces (Barton, Cherkasova, & O'Connor, 2001).

Overall, despite the plot holes, the oversight of voice recognition, the hilariously stereotypical characters, and some less-than-stellar performances, this film offers a relatively accurate representation of prosopagnosia as a neurological disorder. While finer details about the cause of prosopagnosia were left out, the general descriptions of the symptoms and methods of coping are surprisingly accurate. Many of the characters seemed shockingly, almost irritatingly ignorant to the difficulties someone suffering with "face blindness" endures, and Anna fails to use voices - the most telling marker - to identify people she knows. This hackneyed plot wanes to a predictable conclusion. Still, "Faces in the Crowd" does a serviceable job educating viewers on the dramatic emotional toll prosopagnosia can take. (It contains violence and some sexual content.)

References

Barton, J.J.S., Cherkasova, M., & O'Connor, M. (2001). Covert recognition in acquired and developmental prosopagnosia. Neurology, 57, 1161-1168.

Ellis, H.D., & Florence, M. (1990). Bodamer's (1947) paper on prosopagnosia. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 7, 81-105. doi: 10.1080/02643299008253437

Gauthier, I.L., Behrmann, M., & Tarr, M.J. (1999). Can face recognition really be dissociated from object recognition? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 11, 349-370. doi:10.1162/089892999563472

Gazzaniga, M.S., Ivry, R.B., & Mangun, G.R. (2009). Cognitive Neuroscience: the Biology of the Mind. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Ltd.

Kennerknecht, I., Grueter, T., Welling, B., Wentzek, S., Horst, J., Edwards, S., & Grueter, M. (2006). “First report of prevalence of non-syndromic hereditary prosopagnosia (HPA).” American Journal of Medical Genetics, 140A, 1617-1622.

Sacks, O. (1985). The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Other Clinical Tales. New York: Summit Books.

Zillmer, E.A., Spiers, M.V., & Culbertson, W.C. (2008). Principles of Neuropsychology. California: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed