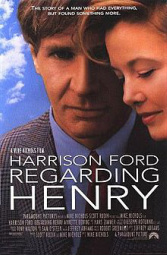

Henry, an aggressive defense lawyer, is shot in the head and shoulder during a robbery. He wakes up in the hospital unable to speak, coordinate his movements, and has extensive memory loss. His doctor explains that interrupted blood flow to the brain resulted in generalized brain damage. During rehabilitation, he is able to regain some verbal ability and motor function, but not his memory. He goes home, and manages to reconnect with the family he barely remembers. He returns to work, but now has ethical concerns with his previous cases. He decides to firmly establish himself as a different person rather than attempting to identify the person he used to be.

Neuropsychological Review

Amnesia and Hollywood: Can Brain Injury Improve Your Life?

Elizabeth K. Whipple

It is a frequent scene in Hollywood, that of a hapless bystander who gets pulled into a disastrous situation that is neither his fault nor under his control. The character must do everything in his power to rise above the situation, to learn and grow in order to overcome...

The majority of Regarding Henry is concerned with Henry regaining his basic functioning, memory, and familial ties. It also chronicles an astonishing personality and behavioral change, where Henry slowly becomes more similar to his idealistic and loving younger self, rather than the disillusioned adult he was at the time of the shooting. In the beginning of the movie, pre-injury, Henry is portrayed as the caricature of a corporate lawyer. He is amoral, selfish, and greedy, only concerned with the bottom line. He is an uninterested and distant father and husband, and prefers to spend his time working instead of engaging with his family. However, after the shooting and subsequent physical and cognitive rehabilitation, Henry begins to show signs of dissatisfaction with his prior persona. This is shown in little ways in the movie (for example, he begins referring to his chauffer and maid by their names for the first time), and Henry’s struggle to reconcile his “real” personality with his corporate lifestyle is made evident. This movie therefore brings up an interesting question—can a brain injury afford a person the opportunity to change for the better? Can it make someone more pleasant to be around socially, more likeable as a person? Can a near-death injury, with very real physical, neurological, and cognitive consequences, end up as a blessing rather than a curse? Regarding Henry seems to make the argument that this positive change is possible and even likely. However, empirical evidence, individual and group case studies, and literature on frontal lobe damage and anoxia seem to point in the other (i.e. less positive) direction. These data on TBI and anoxia suggest that while these injuries are not necessarily life-changing in a detrimental way, they do often result in deficits and impairments that make everyday life activities and social functioning more difficult.

Regarding Henry is a film that deals with the concept of a forgotten identity, but in this script is it not just some memories that are lost. Instead, is a complete mental wipe—Henry has lost the ability to walk, to tie his shoes, to read, to talk, to identify food preferences. He has no memory of his wife, his daughter, or his job as lawyer. He cannot pick up on social nuances or humor, and initially displays a clear disconnect with other people. Yet, as the movie goes on, Henry begins to experience a child-like wonder with the world, and gradually allows his gentle and loving persona to reemerge.

Some of the personality changes the Henry experiences after his injuries are very much in line with what is seen in clinical TBI and anoxia patients. The impaired social judgment is one such common symptom. Individuals with frontal lobe damage often display dramatic deficiencies in social ability, and seem to simply lose their interpersonal skills post-injury (Alexander & Stuss, 2000). Right frontal damage in particular (Henry’s location of trauma) can often result in a flat or humorless presentation, because these individuals are unable to appreciate subtle nuances in conversation. Theory of mind is also often impaired, so they have trouble understanding another’s perspective, which further damages social effectiveness (Chayer & Freedman, 2001). These individuals are often excessively literal and direct, as a result of their inability to make use of abstraction and irony, and this is a trait that Henry clearly displays in his conversation with a waiter during a high-society function. When Sarah asks him what has been going on at the party, he is able to relate the marital struggles of a couple he has overheard others gossip about, but he is unable to understand the deeper meaning of the story and joke that he overheard. Another symptom of both frontal lobe damage and anoxia that Henry is seen struggling with is verbal fluency. Because of the dominant role of the frontal lobe in language, TBI patients often show difficulty with word-finding, syntax, and grammar, and consequently speech is often slowed and reduced in complexity (Alexander & Stuss, 2000; Chayer & Freedman, 2001). Henry clearly shows this struggle in the beginning of his rehabilitation process, where he stammers and has to fight for words.

Despite the accuracy of some of the symptoms that Henry displays, the overall beneficial way that these deficits impact his life and his relationships seems unrealistic. Regarding Henry does a good job showing the confusion, despair, and depression that is associated with memory loss and behavioral change; yet, the take-home message of this film seems to be that brain damage can or will improve the subjective experience of someone’s life. Henry manifests the impulsivity, disinhibition, attentional deficits, and emotional lability that are common after a brain injury (Chayer & Freedman, 2001), but in a way that is child-like and endearing. His wife falls back in love with him, and his daughter finally has a father who pays attention to her. However, clinical evidence shows that these traits generally manifest in a way that is frustrating and potentially dangerous to others, because individuals suffering from brain damage often have difficulty in comprehending the full consequences of their behavior. They display low frustration tolerance levels, poor judgment, indecisiveness, and a loss of impulse control that often manifests as temper tantrums or violence (Caine & Watson, 2000).

Phineas Gage, perhaps the most famous case of frontal lobe damage, was described as “heedless, immoral, and irritable” (Alexander & Stuss, 2000, p. 433) after his injury. However, Henry’s personality does the opposite of Gage’s—he changes from an immoral and irritable person into a lovable and conscientious individual. Although this change is not necessarily impossible, it is in opposition to the most common behavioral manifestations and personality changes after a TBI. Moreover, Regarding Henry mentions but does not fully explore the ways in which these personality changes negatively affect Henry and his family’s life. Henry is unable to continue working, due to both cognitive decline and his newfound moral code, so he quits his job. With the loss of Henry’s vocational status, his wife Sarah becomes an outcast in their social world, and they must sell their expensive apartment. Abrams and Nichols make mention of these issues in the context of Sarah and Henry’s struggle to regain a normal life, but an adequate conclusion is never reached. Instead, these very realistic consequences of brain injury are ignored in favor of demonstrating the ways that Henry’s personality change has brought the family back together. While it is not impossible that brain injury could improve someone’s personality and life the way that this transformation is shown in Regarding Henry is a very one-sided representation of these changes, and is therefore perhaps not an entirely realistic demonstration of the true costs of brain injury.

References

Abrams, J.J. (Producer) & Nichols, M. (Director). (1991). Regarding Henry (Motion

picture). USA: Paramount Pictures.

Alexander, M.P. & Stuss, D.T. (2000). Disorders of frontal lobe functioning. Seminars in

Neurology, 20(4), 427-436.

Caine & Watson, (2000). Neuropsychological and neuropathological sequalae of cerebral anoxia:

A critical review. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 6, 86-99.

Chayer & Freedman, (2001). Frontal lobe functions. Current Neurology and Neuroscience

Reports, 1, 547-552.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed