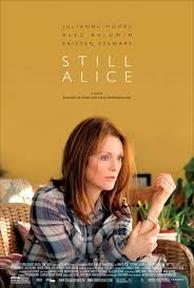

At the top of her game, 50-year-old Alice is diagnosed with a genetically linked, early onset, type of Alzheimer’s Disease. The movie follows an ambitious and intellectual woman through her loss of self with each painful aspect of her decline in memory, communication, and eventually her independence. As she experiences a fundamental loss of who she once was, we observe Alice and her family's adaptation to Alzheimer’s, as they struggle to find hope in an otherwise hopeless situation. Still Alice encourages us to redefine a life worth living when knowledge of ourselves is taken away.

The Changing Self in Alzheimer’s Disease: a Personal Perspective Through “Still Alice”

Daniel G. Smith, M. S. (Contact )

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) can be called the “ultimate thief” insofar as we define ourselves as “the sum of our combined experiences” (Wolfson, 2008). In Still Alice (based on the fictional book I’m Still Alice by neuroscientist Lisa Genova), Julianne Moore gives a stellar portrayal of Alice, a strong woman who must face a life with early-onset (familial) Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). A woman who defines herself by her intellect and strong facility with language must adapt to the many existential dilemmas and at the center, a fundamental loss of self that arises with this chronic, progressive, and at present, incurable condition.

Although AD frequently begins with problems of encoding and remembering new information there is usually an increasing loss of memory for personal events as the disease progresses (Holtzman, Morris, & Goate, 2011). Autobiographical-knowledge is a fundamental component of self-knowledge (Buckner,2007), with self-knowledge typically defining conceptions of self (Dore et al., 2014). Autobiographical memory and memories about relationships with others, both rely upon a constant tracking of events with respect to the self (Buckner, 2007). Theory of mind, the ability to place oneself mentally in the perspective of another, appears to rely in part on intact self-knowledge, and also tends to be impaired in AD throughout the progression of the disease (Moreau et al., 2013).

Language dysfunction, which can also be a symptom of AD (Holtzman, Morris, & Goate, 2011), is particularly damaging to Alice’s sense of self. Along with autobiographical memory, language appears intimately tied to self-knowledge. Alice, a well-respected linguistics professor at a prestigious university, has defined her life through her command of language. It is her difficulties finding words that first reveal that something is wrong. In an early scene as a guest speaker, Alice is able to pass off her difficulties with word finding as “too much wine”. As the movie and stages of the disease progress, Alice’s language problems worsen. In the early stages, Alice’s deficits are characterized by word finding errors in conversation and in an online word game with her daughter. In the moderate stages, we observe greater difficulties in Alice’s comprehension and disorientation during conversations. By the end of the movie, seemingly the severe to advanced stages, Alice becomes almost non-verbal, having difficulties in comprehension, and grunts her initial responses, revealing the potential onset of muteness.

As a final affront to Alice’s self, self-control, personality and mood change and inability to live independently are a part of AD’s progression. For Alice in the moderate stage of the disease, obvious memory problems and difficulty with language are accompanied by what many family members would perceive as personality changes, or reactions to the disease, but can also be related to brain changes that affect the frontal lobes. As the movie and the disease progresses, Alice’s well kempt appearance slowly fades. Alice’s smart suits, straightened hair, and hint of makeup, disappear in favor of more comfortable clothing and less focus on appearance. The way in which she interacts with others similarly changes, as she is frustrated far more easily by slights and suggestions that she is remembering things incorrectly. In the moderate stage, people begin to experience loss of independent function in most activities of daily living and during the severe and advanced stages, are unable to live independently (Holtzman, Morris, & Goate, 2011). For a fiercely ambitious woman like Alice, this loss of independence combines with worsening memory and language changes from the early stage of the disease to the later stages. Together, each stage of the disease and each decline is a particularly egregious offense to Alice’s sense of self.

Not only is Alice’s past lost, so too is her future. Beyond the perception of the self and how we come to relate to others, AD tends to result in a loss of future self and the ability to think about and plan for the future (Klein, 2014; Shacter, 2012). Given Alice’s knowledge of the progressive symptoms of the disease and her fear of losing herself, early on she plans suicide for the time she can no longer answer the memory questions she has made up for herself. Her plan mimics real world considerations for end of life decisions and advanced directives in the US and abroad (de Boer et al., 2011). For Alice, however, her personal directive fails. The later mentally impaired Alice that stumbles upon the message - and the plan for euthanasia - is not sure of the goal of the butterfly folder, and is unable to keep track of its instructions.

Following the botched suicide plan, we are left wondering what’s next for Alice? What defines Alice after much has been taken away and her family begins to separate from her? On a grander scale, what is the purpose of life for an individual robbed of both past and future? In the final moments we are given the possibility that the acknowledgement of love, and the continued ability for connection is what gives Alice’s new life hope and meaning.

This brings us to the overall goal and hope for the movie. Throughout, the purpose and quality of Alice’s life is fundamentally called into question. We are given a close look at Alice and her progression through this devastating disease. We are provided a glimpse into the need for adaption by the individual as well as the family, and by the end of the movie, we are left to question the essential qualities of life apart from our memories and experiences.

From a neuropsychological perspective, while the movie excellently portrays the heart-wrenching loss of self that may come with a diagnosis of AD, it at times inaccurately represents several components of the progression, as well as the manner in which that progression is tracked. For the purpose of time constraints and dramatic movement in the movie we see more immediate progression in memory loss and an overall quick timeline of the disease. However, even in early-onset AD, the progression tends to take place over the course of 10 years, with the early stage lasting 2 – 5 years, the moderate from 2 – 4 years, and the severe and advanced stages characterizing the remainder of life through death (Holtzman, Morris, & Goate, 2011). Given the timing of events in the movie, it appears that Alice progresses from the early to severe stage within a much more constrained time frame, likely 2 to 2.5 years.

Also, possibly due to a need to combine the professional characters of a neuropsychologist and neurologist, the movie takes liberties with the book’s excellent portrayal of the in-depth neuropsychological assessments that take place as a fundamental aspect of the Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis and progression. Rather than the exhaustive battery of tests required to carefully tease the symptoms of AD apart from other dementias, as well as the in-depth interviewing of family members that are typically part and parcel to this diagnosis of exclusion, these roles are seemingly replaced by simplistic indices of cognitive function administered by her neurologist, and similarly an insufficient tracking of progression by way of self-imposed and simplistic memory testing.

Insufficiencies in diagnostic testing as well as the gradual decline along a prolonged timeframe compressed into a matter of several years, may be forgivable as artistic license taken by the directors. As is their intent, the take home message is rather aptly, what is the definition of self, and the meaning of life, in the context of AD? The meaning of life in the context of AD is a question that resonates with the public, and as demonstrated by Still Alice, is not easily addressed . The movie’s message further speaks to the need for greater awareness of the impact of AD, as well as the need for funding of research seeking early diagnosis and treatment of AD. Alice, as excellently portrayed by Julianne Moore, may well serve as a symbol for the need for progress toward the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, as well as a model of the possibility for continued relationship for family’s suffering from the disease.

References:

Buckner, R. L., & Carroll, D. C. (2007). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(2), 49-57.

de Boer, M. E., Dröes, R. M., Jonker, C., Eefsting, J. A., & Hertogh, C. M. (2011). Advance directives for euthanasia in dementia: how do they affect resident care in Dutch nursing homes? Experiences of physicians and relatives.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(6), 989-996.

Doré, B.P., et al., Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core systems, in APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Mikulincer, M., et al., (Eds). 2014, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. p. 693-720.

Holtzman, D. M., Morris, J. C., & Goate, A. M. (2011). Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Science translational medicine, 3(77), 77sr1-77sr1.

Klein, S. B. (2015). What memory is. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 6(1), 1-38.

Leyhe, T., Müller, S., Milian, M., Eschweiler, G. W., & Saur, R. (2009). Impairment of episodic and semantic autobiographical memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia,47(12), 2464-2469.

Moreau, N., Rauzy, S., Bonnefoi, B., Renié, L., Martinez-Almoyna, L., Viallet, F., & Champagne-Lavau, M. (in press). Different Patterns of Theory of Mind Impairment in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

Schacter, D. L. (2012). Adaptive constructive processes and the future of memory. American Psychologist, 67(8), 603.

Wolfson, W. (2008). Unraveling the tangled brain of Alzheimer's. Chemistry & biology, 15(2), 89-90.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed