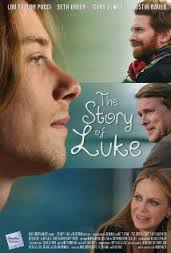

Luke's rigid lifestyle is disrupted when his grandmother and primary caretaker passes away forcing Luke and his grandfather to move in with Luke’s dysfunctional family. Not wanting to be a burden to his family or to be viewed as disabled due to his autistic spectrum diagnosis, Luke embarks on a journey to gain independence and demonstrate that he is just as capable as any other member of society. Heeding his grandfather’s advice, he sets out to obtain a job and then find love, two factors that his grandfather tells him are necessities in life. In his quest, Luke learns how to cope with his condition while changing the lives of those he encounters in the process.

Neuropsychological Review

Social Perception Technology in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Adept or Just Pretending?

Mary V. Spiers & Kristina E. Patrick

Previously published in Spiers, M.V. & Patrick K. E. (2013) Social perception technology in autism spectrum disorder: Adept or “just pretending”? [Review of film (2012) The Story of Luke]. PsycCRITIQUES, 58(34), Doi: 10.1037/a0033962.

Copyright APA. This article may not exactly replicate the final version published in the APA journal. It is not the copy of record.

The Story of Luke (2012) explores relationship issues in a young man with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) who is on a quest for an independent life...

The Story of Luke is one of the few movies to consider the gamut of relationships for individuals with ASD. For Luke, these relationships include his grandfather, his estranged mother, his newfound family, coworkers and a woman he would like to date. The relationships are new, and Luke navigates some with more success than others. He attempts to follow his grandfather’s advice to “get a job” and “get a girl” in a prescriptive manner, by following rules. However, he appears much more intuitive than expected in discerning the emotional landscape of his family. The movie inserts many stereotypical emotional behaviors of ASD such as Luke’s tendency to literally interpret and parrot directives and phrases and to do so at socially inappropriate times. Oddly, even though Luke has extreme difficulty in reading some situations, appropriately expressing emotion, and using appropriate vocal tone and pitch, he also appears to perceive and respond to subtle emotional cues from his family. For example, Luke quickly adjusts his behavior to his high-strung aunt and eventually gives her advice on how to deal with stress. Luke even appears to know his uncle better than his uncle knows himself, making it seem as though Luke has highly developed social perception skills. In addition, stereotypical misperceptions from others that Luke must repeatedly correct (being called a “retard”, or assumptions that he is a savant) are also contrasted with characters that are surprisingly tolerant of his socially inappropriate language. In the end, the composite of ASD as it is portrayed in Luke, and reacted to by others, seems inconsistent and likely chosen for comedic effect rather than accuracy.

In dealing with the larger theme of the movie, however, The Story of Luke raises an important question related to whether someone with ASD can actually learn and incorporate social communication skills in a natural manner or if s/he will always be “just pretending”, as proclaimed by Luke’s constantly negative and berating coworker Zack. This issue is reminiscent of ASD spokesperson Temple Grandin’s reference to herself as an “Anthropologist on Mars” while describing her relationship with neurotypical (NT) society (Sachs, 1995).

Motivated by his desire to find a girlfriend, Luke attempts to improve his social perception skills via a “girlfriend” avatar developed by Zack to practice mating rituals of NT’s. Avatars of desirable women are programmed to respond to emotional expressions and social interaction according to a measure of the female’s tendency to be offended by inappropriate social behavior. The program operates as a two-way virtual reality system in which the avatar both initiates interaction with and responds to Luke. When Luke correctly interprets the avatar’s social cues and responds appropriately, she becomes more interested in him; when he responds inappropriately, she shows expressions of anger or disgust. Through this program, Luke practices simulated interactions with the woman he wants to ask out for a date, improving his social perception skills and building his confidence.

In recent years, numerous computerized gaming programs have been developed with the goal of increasing social perception skills in individuals with ASD. Although technology has not yet developed to the level of Zack’s program, an interactive system like Zack’s seems to be some game developers’ ultimate goal. Currently, the majority of social perception games marketed towards individuals with ASD involve one-way interactions. For instance, several computer programs display faces with various expressions with the goal of teaching children with ASD how to recognize complex emotional states (Golan & Baron-Cohen, 2006; Hopkins, 2007; Tanaka et al, 2010). Similarly, in an animation series called The Transporters, vehicles, which are commonly a narrow interest for individuals with ASD, have human faces and are used to teach emotional comprehension (Golan & Baron-Cohen, 2006). Although these programs have demonstrated some level of effectiveness for improving facial and emotional recognition, they are limited in that they do not give users the opportunity to practice emotional expression or appropriate social interaction.

Recently, games targeted at improving social perception have become more interactive. Several games designed for individuals with ASD use eye-tracking and webcams to evaluate users’ responses. Some require players to produce specific facial expressions in order to pass obstacles or advance to new levels (Cockburn et al., 2008; Kohls & Schultz, 2011). In a virtual reality program developed at the MIND Institute (Mundy, 2011), users practice answering questions about themselves to peers. If the player looks away from the peer for too long during the conversation, the peer begins to fade away, providing a cue to the user to continue attending to the peer’s face. These games allow users to learn skills in the context of an activity that is intrinsically rewarding and delivers immediate reinforcement. One of the major benefits of these games is that they are self-directed and do not require intensive case management (Kohls & Schultz, 2011).

The newest social perception games involve use of avatars like the one designed by Zack in The Story of Luke. These programs are in early stages of development. At this stage, the role of the avatars is primarily limited to imitating facial expressions produced by the user (Cockburn et al., 2008). In another advancement, a series of computer games called LIFEisGAME allow the player to create his or her own story by forming facial expressions (Miranda, Fernandes, & Sousa, 2011). An avatar proceeds through a story until reaching a situation that requires an emotional reaction. Based on the facial expression produced by the player, the story evolves. For instance, if the player reacts with an expression recognized as “sad” by the motion capture software, the story progresses in a manner congruent with a sad character. Although this is an improvement in interactive technology aimed at increasing social perception skills, the ultimate goal for use of 3D avatars in these games is for the avatar to interact with and respond to the user (Orvalho, Miranda, & Sousa, 2009). Creation of complex avatars like the one designed by Zack would allow for even more nuanced social interactions and better generalization because the avatars could be programmed with different “personalities.”

Whether practicing social skills with avatars can successfully generalize to intricate and varied social communication is yet to be seen but The Story of Luke raises important questions about the promise and limits of technology. Even if virtual reality technology can help individuals with ASD navigate and respond to social situations, it is unlikely to work as quickly as portrayed in The Story of Luke. Interventions aimed at improving social perception in the ASD population are most likely to be effective if they are implemented early before rigid patterns develop. In the end, for Luke, his newfound social skills did not get him the girl, which seems to be in line with the real difficulties people with ASD face, but they gave him the confidence that he could attract one of the other “3.2 billion females on the planet.”

References

Cockburn, J., Bartlett, M., Tanaka, J., Movellan, J., Pierce, M. & Schultz, R. (2008). SmileMaze: A tutoring system in real-time facial expression perception and production in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Proceedings from the IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition, 978-986.

Golan, O. & Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). Sytemizing empathy: Teaching adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism to recognize complex emotions using interactive multimedia. Development and Psychopathology, 18(2), 591-617.

Hopkins, I. M. (2007). Demonstration and evaluation of avatar assistant: Encouraging social development in children with autism spectrum disorders. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama at Birmingham).

Kohls, G. & Schultz, R.T. (2011). Computerized health games to promote social perceptual learning in autism. Autism Spectrum News, Summer 2011, 18, 31.

Miranda, J.C., Fernandes, T., & Sousa, A.A. (2011). Interactive technology: Teaching people with autism to recognize facial emotions. In Williams, T. (Ed.), Autism spectrum disorders-From genes to environment. Online: InTech. DOI: 10.5772/747.

Mundy, P. (2011). Autism, social attention & virtual reality treatment applications for higher functioning children with autism. MIND Institute Lecture Series on Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Lecture retrieved from http://www.uctv.tv/shows/Autism-Social-Attention-Virtual-Reality-Treatment-Applications-for-Higher-Functioning-Children-with-Autism-20277.

Orvalho, V., Miranda, J., & Sousa, A.A. (2009). Facial synthesys of 3D avatars for therapeutic applications. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 144, 96-98.

Sacks, Oliver. (1995). An Anthropologist on Mars. In An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales (pp. 244-296). New York: Alfred A Knopf, Inc.

Tanaka, J., Wolf, J., Klaiman, C., Koenig, K., Cockburn, J., Herlihy, L., Brown, C., Stahl, S., Kaiser, M.D., & Schultz, R.T. (2010). Using computerized games to teach face recognition skills to children with autism spectrum disorder: the Let’s Face It! program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 51(8), 944-952.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed