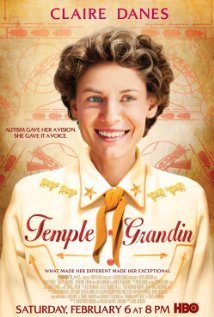

| A young woman with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) shows the ability to “think in pictures” and overcomes immense obstacles to achieve extraordinary goals. In this biopic of Temple Grandin, the celebrated woman with ASD, the struggles and triumphs of her early life are chronicled. With a comprehensive support network Temple learns to communicate, to discover how her brain works, and to accept her unique talents which ultimately lead to valuable contributions in animal husbandry and our understanding of people on the autism spectrum. |

Different, Not Less

Nicole Roshannon

“They knew I was different, but not less”; proudly proclaims a young Temple Grandin, during a sure-to-give-you-goose-bumps speech in the last scene of Mick Jackson’s HBO biopic detailing Grandin’s life as an autistic person. While the public’s awareness of autism has increased over the past several decades, so grew Grandin’s celebrity as an inspiring autist and self advocate.

The beef and potatoes of this film takes place during the cumbersome and painful early chapters of Grandin’s life with autism, before the days where the back-sides of minivans were adorned with puzzle-piece ribbon magnets. Dane’s physical and prosody-perfect transformation into the youthful Temple featured here is nothing short of uncanny.

This film aims to tell a tale of what it takes to overcome the plethora of adversity associated with an autism diagnosis. It takes the viewer through the frustration faced by both mother and child during Temple’s speechless pre-school years, educational ostracism, peer rejection, and abundant sexism in the male dominated cattle handling industry suffered by Temple during the 60’s and 70’s. Over the course of one hundred, forty nine minutes, the film highlights how a comprehensive support network of dedicated family members and educators insistent on early intervention and innovative teaching methods centered around her “visual thinking”, contribute Temple’s extraordinary outcome.

Grandin describes the concept of visual thinking in her novel Thinking in Pictures and Other Reports From my Life with Autism (1995). She describes her ability to “translate both spoken and written words into full-color movies, complete with sound, which run like a VCR tape in my head.” In the cinematographically impressive “shoe” scene, in which Temple’s science teacher Dr. Harlock, carefully uncovers her unusual thinking style, the film’s director gives us a dead-on visualization of Temple’s somewhat abstracted description. The notion of “thinking in pictures”, or visual thinking is common among autistic persons, as is thinking in patterns or word details (Grandin, 1995). Interestingly, this propensity for specialized thinking among autists is thought to be a compensatory adaptation to the suspected underconnectivity in various cortical brain regions (Kana et al., 2006; Courschsne et al., 2001).

Once Dr. Carlock uncovers how Temple thinks, he is able to understand how she learns, a puzzle often faced by many professionals or family members working with autists. In the scene where Dr. Carlock invites Temple to re-create the classic “Ames Room” optical illusion using horses for extra-credit, we see very clearly that by developing Temple’s strengths as a visually and spatially oriented thinker through challenging her with an innovative design-oriented task, she is able to exceed and thereby express her truly unique talents.

This is also the first time during the film where her peers seem to begin to appreciate her as different, not less. In her novel, Thinking in Pictures and Other Reports From my Life with Autism (1995), Dr. Grandin addresses the awesome importance of educators, such as we see here in the realization of her grade school mentor's willingness to explore and emphasize the strengths of autistic students instead of merely focusing on deficits. Throughout many scenes, the film hammers home the social and cultural significance of not only appreciating, but also valuing the specialized thinking and strengths of autistic persons.

During a haunting flashback into Grandin’s childhood of a strained teaching session, we see Eustacia, Temple’s mother, trying desperately to elicit speech from her daughter by repetitively showing her flashcards while simultaneously enunciating words. Temple, instead of paying attention to her mother, let alone verbally responding to her, stares blankly at a light fixture with hanging crystals while experiencing a spell of sensory overload from the slight sound emitted by the light.

One common feature of disordered communication presented in autistic persons is a lack of expressive speech. Emerging on the scene in the early 1980’s, various behaviorist treatment methods geared towards not only modifying behavior but also teaching language (a notion that will make any cognitive psychologist or psycholinguist cringe) were developed to address this deficit. A majority of early intervention techniques in the field seem to be centered around an autistic person’s aptitude for visual thinking, including as picture communication exchange (PECs) and TEACCH method, which uses visual organization to teach language (Kana et al., 2006). In her book, Temple credits her mother with helping her learn to effectively communicate through consistently using flashcards which paired 100’s of pictures with words, an intervention she started with her daughter during her second year. While some may view this as merely an anecdotal account of success, evidence does suggest that early intervention methods in the treatment of symptoms of autism do produce positive outcomes, particularly in the domains of IQ score and modifying behavior (Rogers and Vismara, 2008).

The movie’s portrayal of Temple Grandin’s early life with autism is as successful and as inspiring as it gets. At the end of the day and at the end of the film it is important to remember that individuals with autism are just that, individuals. Everyone’s journey with overcoming and embracing the ups and downs of autism is different, and this movie is careful to show that Temple was lucky that things seem to fall in place for her.

Her story shows us that with the right cocktail of a strong support network , early intervention, innovative educational accommodations, personal perseverance, and self sufficiency, a remarkable outcome is entirely possible for a person with an autism spectrum disorder. We see how the influential people in Temple’s early life encouraged developing her strengths instead of merely focusing on modifying her weaknesses, a very simple and entirely realistic thought.

It is also important to note that this film strongly captures Temple’s anti-cure perspective, which is central to acceptance of neurodiversity and the autism rights movement. For Dr. Grandin and many others, autism should not be conceptualized as a disease to be cured, but instead, as a natural variation in functioning. In spite of her struggles through life, we see here how Temple has an incredible ability to think differently than the rest of us; and that is nothing short of a true gift. This film gets a giant, red, A+.

References

Courchesne, E., Karns, C.M., Davis, H.R., Ziccardi, R., Carper, R.A., and Tigue, Z.D. (2001).Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder.an MRI study. Neurology, 57, 245–254.

Grandin, T. (1995). Thinking in pictures and other reports from my life with autism. New York, NY: Vintage.

Just, M.A., Cherkassky, V.L., Keller, T.A., Minshew, N.J.(2004).Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain,127,1811-1821.

Kana, R. A., Keller, T., Cherkassy, V. L., Minshew, N. J, and M. A. Just. (2006). Sentence comprehension in autism: thinking in pictures with decreased functional connectivity. Brain, 129, 2484-2493.

Rogers, S. J. and Vismara, L. A. (2008). Evidence based intervention treatments for early autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 8-38.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed